What Happens to Medical Samples Between Patient and Result?

(Because Every Result Depends on What Happened in Between)

At 8:12 a.m., a phlebotomist named Maria draws blood from a patient, Mr. Johnson, at a busy outpatient collection center.

The tubes are labeled, placed in a rack, and set aside for the 10 a.m. courier pickup.

By 2:30 p.m., in a different part of the city, Dr. Lee, Lab Director at the regional diagnostics lab, is staring at a QC flag on her screen.

A chemistry panel has failed. Again.

The instruments are fine. Reagents are in date. The problem is somewhere in the journey between Maria’s draw chair and Dr. Lee’s analyzer.

Most Labs call this the pre-analytical phase. And depending on the study you read, 46–70% of all lab errors happen here, before a sample ever reaches the analyzer. Many of them tie back to collection, labeling, handling, and transport.

This is the story of that journey—and all the places where temperature, light, shock, and time can quietly change a result.

Video: Watch this quick visual overview of the medical sample journey.

Step 1: The Draw – Where the Journey Starts

For Maria, the morning is a blur of patients.

She checks IDs, confirms orders, chooses tubes, and follows the draw sequence. For certain analytes, she has to remember extra rules:

- Protect this tube from light (bilirubin, some vitamins, porphyrins).

- Get this sample to the lab quickly or separate within a couple of hours (glucose, potassium, some coag tests).

Already, the first set of risks appear:

- The sample may sit on the bench or a lockbox, in a sunlit collection bay.

- It may be left at room temperature when it should be refrigerated or kept chilled.

- Tubes might not be inverted correctly or in time, affecting clot formation and cellular components.

Most of this is invisible. The tube looks fine. But the clock has started.

Where excursions can creep in

- Temperature: Sample trays near a window, under a warm lamp, or in an overfilled, inconsistent refrigerator.

- Light: Clear tubes with bilirubin or other light-sensitive analytes left under bright room lights. Even a couple of hours of exposure can start to change concentrations.

- Time: Delays before centrifugation or transport can alter glucose, potassium, and other analytes.

Step 2: Handover to the Courier – A New Set of Risks

At 10:03 a.m., Mike, the medical courier, signs for the samples.

He has six stops on this route. He’s racing traffic, construction zones, and the lunch hour. Some clinics hand him insulated containers with ice packs. Others pass him a basic transport box with minimal temperature control. Even when insulated, studies show that many transport boxes fail to keep internal temperature stable over the full route time, especially in hot weather.

Mike loads everything into the back of his car.

What can go wrong between clinic and lab?

- Heat in the vehicle: Even in moderate climates, the temperature in a parked or slow-moving car can climb quickly, pushing specimens outside of their required 2–8°C or frozen ranges.

- Cold shock in winter: Without protection, samples can be exposed to near-freezing temperatures or cycles of cold–warm–cold that stress cells and proteins.

- Mechanical shock and vibration: Potholes, speed bumps, abrupt braking, or pneumatic tube systems can cause agitation and shear forces that contribute to hemolysis or other changes.

- Light exposure: Boxes opened repeatedly at each stop,briefly exposing samples to bright sunlight during transfers, especially problematic for light-sensitive analytes.

Again, the tubes still look fine. But at the molecular level, analytes can begin to drift.

Step 3: The Regional Hub – Hidden in Plain Sight

Many diagnostics networks run on a hub-and-spoke model:

- Samples move from small collection sites to regional hubs

- Then from regional hubs to central labs for specialized testing

At the regional hub, Aisha, a lab technician, scans barcodes and sorts samples for different analyzers and outbound shipments.

She does everything she can to work quickly and by the book. But she fights the realities of the environment:

- Limited refrigerated space

- Busy benches where tubes may sit at room temperature

- Transport containers that arrive over-packed or under-conditioned

- Occasional waiting time before outbound couriers depart for the central lab

Guidelines from organizations like CLSI emphasize that the pre-analytical process ends only when the analytical procedure begins—and that errors in collection, labeling, transport, and storage are the most frequent lab errors.

New excursion risks at the hub

- Cumulative temperature stress: Samples that were warm in the van may now be cooled… but after damage has already started.

- Reconditioning mistakes: Overpacking with ice or dry ice for some tests, causing overcooling when room temperature was recommended (e.g., certain coagulation or blood gas specimens).

- Repeat handling and shock: Tubes are lifted, sorted, dropped into racks, sometimes moved via belt systems or pneumatic tubes. Each step adds mechanical load.

- Light for specialized analytes: Samples for bilirubin, some vitamins, and porphyrins that weren’t properly shielded from light can start to drift low, risking underestimation.

None of this is malicious. It’s the reality of a high-throughput system run by people who care—but who don’t always have the right tools, feedback and working environment.

Step 4: Central Lab – Where Problems Finally Surface

By the time samples reach the central lab, multiple hours may have passed.

They’ve been through:

- At least one courier route

- One or two hubs or sorting points

- Multiple handovers, openings, and repackings

In the central lab, instruments are calibrated, controls are in, and analytics are tightly controlled. Here, Dr. Lee and her team work in a highly standardized environment.

But the analyzers can only work with what they receive.

How excursions show up in results

- QC failures: Changes in analytes from temperature, time, or hemolysis may cause QC to fail, triggering investigations and reruns.

- Subtle drifts: Not every damaged sample triggers a clear flag. Some slip through with shifted values—high enough or low enough to influence clinical decisions, but not obviously “wrong.”

- Repeat testing and redraws: Questionable results mean patients are called back. For them, it’s another needle, another wait, another bill. For the lab, it’s lost time, lost reagents, and lost trust.

This is where the impact on reputation really lands.

From the clinician’s point of view, the lab is “unreliable.” From the patient’s point of view, the healthcare system is fumbling. Over time, referring physicians may:

- Send critical tests elsewhere

- Double-check results with repeat labs

- Question the lab’s overall quality and reliability

Once lost, that trust is extremely hard to rebuild.

The Common Thread: Pre-Analytical Risk You Can’t See

If we zoom out across this whole journey—from Maria’s draw chair to Dr. Lee’s analyzer—four invisible threats keep showing up:

- Temperature excursions

- Samples meant to stay at 2–8°C, -20°C, or room temperature are exposed to the wrong ranges in cars, hallways, and storage areas.(Read more)

- Light exposure

- Mechanical shock and vibration

- Time delays

Together, these factors drive a large portion of pre-analytical error—errors that may account for up to 70% of total lab mistakes.

And yet, most of the time, the tubes look perfectly normal when they arrive.

How Labs Are Re-Thinking Their Cold Chain

Forward-looking diagnostic labs are starting to treat the pre-analytical journey with the same seriousness as their analyzers:

- Standardizing packaging and transport workflows across sites

- Using validated, digitized, and multi-use smart shippers designed to maintain temperature for the full duration of the journey—even in worst-case routes and weather.

- Protecting light-sensitive samples with amber tubes, foil wrapping, and “dark zones” along the workflow.

- Reducing mechanical shock with better handling procedures and more appropriate transport systems.

- Implementing real-time or journey-based monitoring to track temperature and sometimes shock, with audit-ready records that support ISO 15189 and other accreditation requirements.

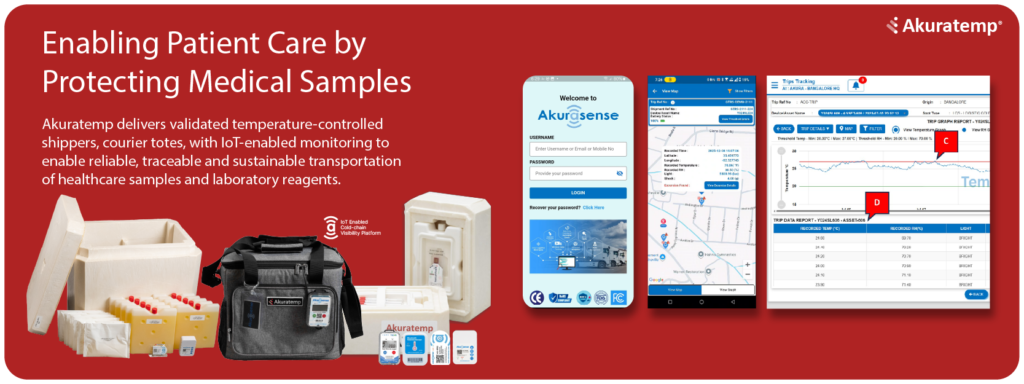

This is exactly the gap Akuratemp focuses on:

- Validated, digitized, multi-use shippers and courier totes designed for healthcare and diagnostic workflows, keeping samples in range across same-day courier routes and multi-day shipments.

- Connected monitoring that captures a documented story of time, temperature, and chain of custody—turning a previously invisible journey into data you can trust and act on.

For most labs, the analyzers, LIS, and reporting workflows are well-controlled and heavily scrutinized.

The weak point—the part that quietly erodes accuracy and reputation—is everything that happens before the sample reaches the analyzer. Your lab’s reputation is shaped long before a result prints. When labs secure the vulnerable miles—temperature, light, shock, and time—they don’t just protect samples. They protect patients, decisions, and the trust that makes their lab the first choice, not the fallback, for clinicians and healthcare systems.

Schedule a conversation with Akuratemp, and together we’ll map your sample journey, close the gaps you can’t see today, and build a cold chain your patients, clinicians, and regulators can all stand behind.